Biography

Hi—this is a biography I initially wrote in December 2023, and have since updated over the years. It details my beliefs, my childhood, and my career. I consider it the best way of getting to know me!

Who am I?

From a birds eye view, I am:

- A tech optimist: I think that salvation lies in technological growth, and that continuing to build on the advancements of our forefathers will solve most of our problems (including things like the environment, our current political enmity, population concerns, etc).

- A socialite: I'm great at meeting people, delivering talks, and building relationships. I'm usually referred to as "outgoing", and my friends/associates are often impressed at how easily I strike up conversations with strangers.

- An opportunist: Although I like to think that my career choices have been deliberate and well-planned, most of my successes involve me stumbling on, and then taking advantage of, short term opportunities. In simple terms, I act first, and figure things out later.

A brief history

How did I become the above? Here's a walk through my 29-odd years, with an emphasis on my entrepreneurial pursuits.

My early life

My family immigrated from Eastern Europe during the fall of communism, and they struggled greatly when they first arrived. The abrupt transition in economic systems, combined with unfortunate personal circumstances, led to some terribly difficult financial times.

Money was tight for most of my childhood. But my parents were gracious enough to never let me know it. They worked several jobs, often fourteen or fifteen hours a day, yet still found moments to spend with me in the evenings or early mornings. I can't remember either of them ever complaining.

Because of that work, they were able to claw themselves out of debt. They eventually purchased a modest apartment at the beginning of a real estate boom in Vancouver, B.C, which helped cement us firmly in the middle class. After I was ten or so, money stopped being the major pressing concern.

School

When I was 7, my teacher recommended I skip the fourth grade. The next year, she suggested I skip another, but my parents relented, saying that it would stunt me socially. I think they were right.

All I did in primary school, really, was read. I'd prowl the library every morning and afternoon (usually gravitating to the fiction section) and devour every story I could find. This was academically beneficial, but socially isolating—I didn't have many friends and spent most of my recreational time alone.

Secondary school was similar, although in the latter years I came out of my shell and made quite a few connections. I still communicate with one regularly.

Early adulthood & university

When I entered university, I initially wanted to become a psychologist. Then a surgeon. Then a world-famous neuroscientist. These were certainly ambitious goals, but most of them were idle fancy—I had little clue how hospitals or laboratories really worked, and in hindsight, my desires were more reflections of the protagonists I had read as a child than they were realistic aims.

I discussed my dreams with several advisors, and they recommended I work in a lab (and later volunteer at a hospital). So in my third year I applied to a handful of grants, and was lucky enough to win a little under $5,000 for peripheral nervous system research. This was the beginning of my disillusionment with academia.

During the grant, I performed a handful of common "research assistant" tasks, like artery dissections and chemistry, for a paper on the vesicular nucleotide transporter (which we later published—how cool!)

Going through the process was interesting, but I distinctly remember being unable to shake the notion that my work felt, for lack of a better word, pointless.

To make a long story short, this research was a very small iterative improvement on a body of knowledge that had no immediate applicability in humans. Nor did it have any real positive implications to animal health, or drug discoveries, or really anything that might be considered cool or worthwhile.

That's all my humble opinion, of course. Some people certainly do find that kind of work valuable, and it's possible I'm just missing something. But either way, after that, I stopped pursuing research as a career. I also began questioning the value of academia more generally, which led me to skipping the majority of my classes.

Promotions company

A few months later, I started my first company with a few friends. I would consider this an entrepreneurial awakening, of sorts, and it occurred mostly through happenstance.

It was a promotions business; we held events at nightclubs in downtown Vancouver, and received a cut of liquor and ticket sales.

TLDR:

- After my grant ended, my friends and I threw a few successful parties on-campus.

- Initially, they were free. But after the first few hundred people showed up, we began charging $5 for entry.

- Our parties were well-liked, and, given their popularity in the university, word eventually got around to faculty as to who was responsible.

- The school didn't like this; there were even some talks of expulsion!

- But one of my friends had a very bright idea. He asked "Can't we just do this legally? I mean, we're of age. If we threw it at the local pub we'd even be making the university some money".

- Faculty agreed, and we threw our first university-sanctioned event the next month.

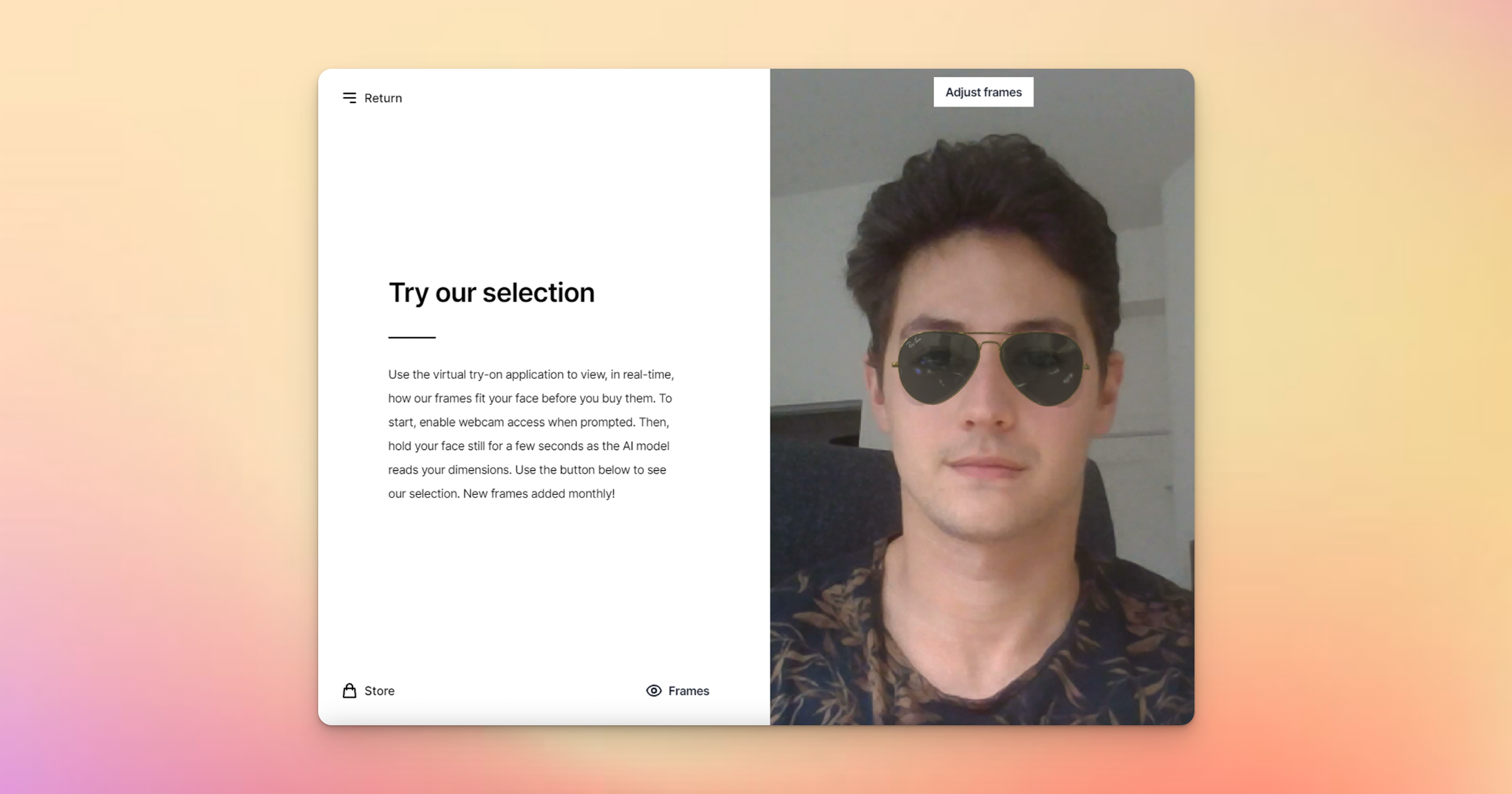

That friend became one of my best, by the way. I think, if he hadn't spoken up when he did, I'd have chosen academia or medicine and grown up to (mostly) hate my life. Here's us at a wedding:

My friends and I called the company Savage Entertainment. We made around $30,000 over ~eighteen months—in hindsight, a pretty paltry sum of money.

But I was deeply drawn to the impact that I made while running that business. In contrast to my time at the lab, I could spend just a few hours per week and touch thousands of lives. In addition, how I used my time was entirely up to me. The freedom was both exciting and a little bit scary.

Online courses on Udemy & Skillshare

The next year, I made a friend at a lecture, and he randomly asked me if I'd ever read The Four Hour Work Week by Tim Ferris. I said no, and he gifted me a copy.

Like many young men who have read Tim Ferris' work, I was hooked instantly. We met up the week after and started discussing business ideas that satisfied the Four Hour constraint.

One of them was an online course company. My friend had a cousin who was making a few hundred dollars each month selling videos on Udemy. I was reasonably confident on camera at that point—I'd filmed a few promotional videos with the prior company—so I told him that sounded like a grand idea, and suggested we film our first course the next week. He would be the cameraman/editor, and I would be the scriptwriter/speaker.

We ended up producing around twenty courses over the course of two years, and hosting them on Udemy along with a few other platforms. They made us over $80,000 for an investment of ~$2K and a few hundred hours.

It was another clear sign to me that you could generate outsized results if you wandered off the beaten path!

Door-to-door sales

A few months after the course business, I graduated. My dabbling in entrepreneurship had made some money, but it was insufficient to build a life with and I was starting to realize my career prospects were thin.

I had a friend who was selling B2B software door-to-door at the time. Over lunch, he wowed me with dollar-figures and explained how easy it was if you just "never stopped hustling". He said I'd be great at it, given my social nature, and invited me to come with him the next time he canvassed. I was flattered.

The next day, I pretended to be his partner and joined him as he booked meetings with a variety of small business owners. It was exhilarating. He didn't make any money, but seeing him convince several complete strangers that his service was valuable enough to book a meeting for was so impressive I started a business within the week.

I sold local marketing services. Most of the companies I was canvassing were brick-and-mortar locations with scant technical knowhow, so my pitch of $200 to put you on the map! was surprisingly effective.

Eventually, my friend joined my company. With his experience (and, frankly, confidence), we began selling larger marketing packages that included comprehensive SEO plans, ads, etc. Within the year, we'd generated well over $150,000, and even started hiring.

It was my first taste of what I'd consider a real company. We hit ~$20,000 one month, and I remember it like it was yesterday.

My partner and I would end up splitting up over conflicting goals. In the grand scheme of things, it was a minor issue. We're still great friends to this day, and I consider leaving to have been essential to my career growth.

Videography

After that, I started a videography business. It was my first solo venture, and I leaned heavily on the experience of my previous company. We shot weddings, corporate videos, and real estate listings.

Initially, I found leads by cold calling. When this proved ineffective, I built an SEO funnel and had some success with paid advertising.

I worked with a variety of contractors, many of which were friends, and later partnered with one. In the last month we made a little over $10,000.

That's when COVID-19 hit. Our local government put a hard cap on events where more than 3 people gathered, which naturally included corporate shoots and weddings. Sooo.. our revenue dropped to $0 overnight.

I was crushed. Many days were spent wandering aimlessly, wondering if I was in over my head. My roommate was the only thing that kept me sane—and I am forever grateful to him for helping me through that time.

Freelance software

At some point, restlessness overpowered my melancholy and I started thinking about what to do next.

My videography company had been location-dependent—it relied on the particulars of the Vancouver market. Were that market to be shut down because of outside events (like COVID-19) it is natural that I would suffer.

On the other hand, software businesses are location-independent. I.e it is much more difficult to shut down the internet than it is to shut down a local municipality, and COVID or no COVID, had I been in software initially I would still have had an income. So I saw this shift as a way to provide me both safety and freedom.

I was mostly interested in machine learning, since I thought it had the highest chances of a disproportionate impact in the next few years. So I began playing around with a few toy models, and eventually decided I would take programming more seriously.

Initially I was going to do a bootcamp, but I worried about gaps in my education. I elected to self-study using resources like Teach Yourself CS and OSSU.

It took a little over five months. During that time, I created an Upwork account and began working as a freelance developer, building frontend apps and sites for clients.

1SecondPainting

Then, one late night, while reading a forum post on programming, I stumbled on Gwern's This Anime Does Not Exist.

To make a long story short: Gwern, a prolific hacker, had put together a way to generate thousands of high-quality cartoon characters in moments with AI. Each one of these cartoon characters would have previously taken hours (or days) to draw by hand.

I didn't understand all of his post, but it seemed clear to me that image generators would soon disrupt design. Programming was top-of-mind, so I decided my next step was to create a software application that could generate impressive-looking images, and then sell those on the Internet.

Initially, I chose to make an architecture generator. I forked one of the base models—StyleGAN—and attempted to fine-tune it on a dataset of buildings, skyscrapers, and drawings. I showed one of the generations to a friend of mine... and his response was something like "that looks nothing like a building and you should give up".

Crushing.

But, to his credit, he followed it up with "you know, it kind of reminds me of the sort of abstract art you'd see in a museum".

This got me thinking!

Art datasets were much easier to acquire, so why not try just feeding it a bunch of art?

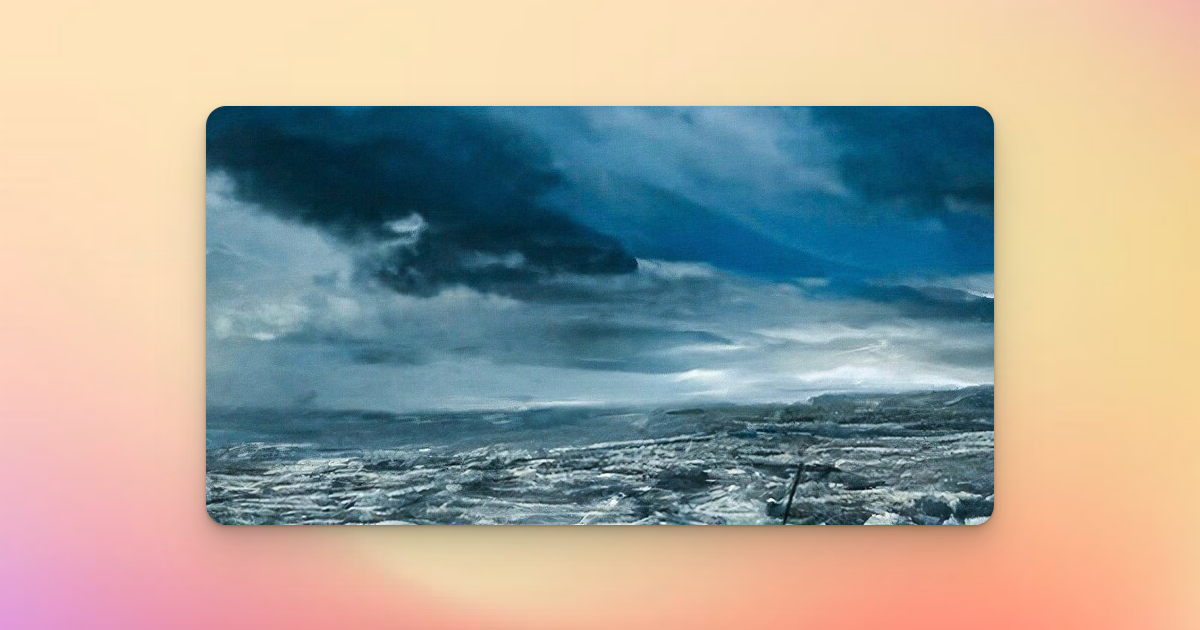

I fine-tuned a fourth model on abstract artists like Kandinsky and Pollock, just to see what it would look like. The results looked okay (to me, anyway).

So on a whim, I made a small web app and posted it on Hacker News before I went to bed that night.

Shockingly, I went viral, hit #1 a few hours later, and by the next afternoon, I had several dozen requests from labs, journals, magazines, and companies to discuss the project.

Keep in mind that AI art, at that point, was an oxymoron—no one had ever seen, nor appreciated, that machines were capable of producing such feats—so anything even remotely creative was considered magic. Seems like a lifetime ago.

My dev skills were not strong enough to implement a sign-up mechanism in time for the traffic spike, so I missed most of the opportunity. But I did eventually add the ability to buy generated art using my platform a few weeks later.

It peaked at ~$2,200 per month (mostly owing to the increasing popularity of NFTs at the time), and I sold the site to a private investor in the US the next year.

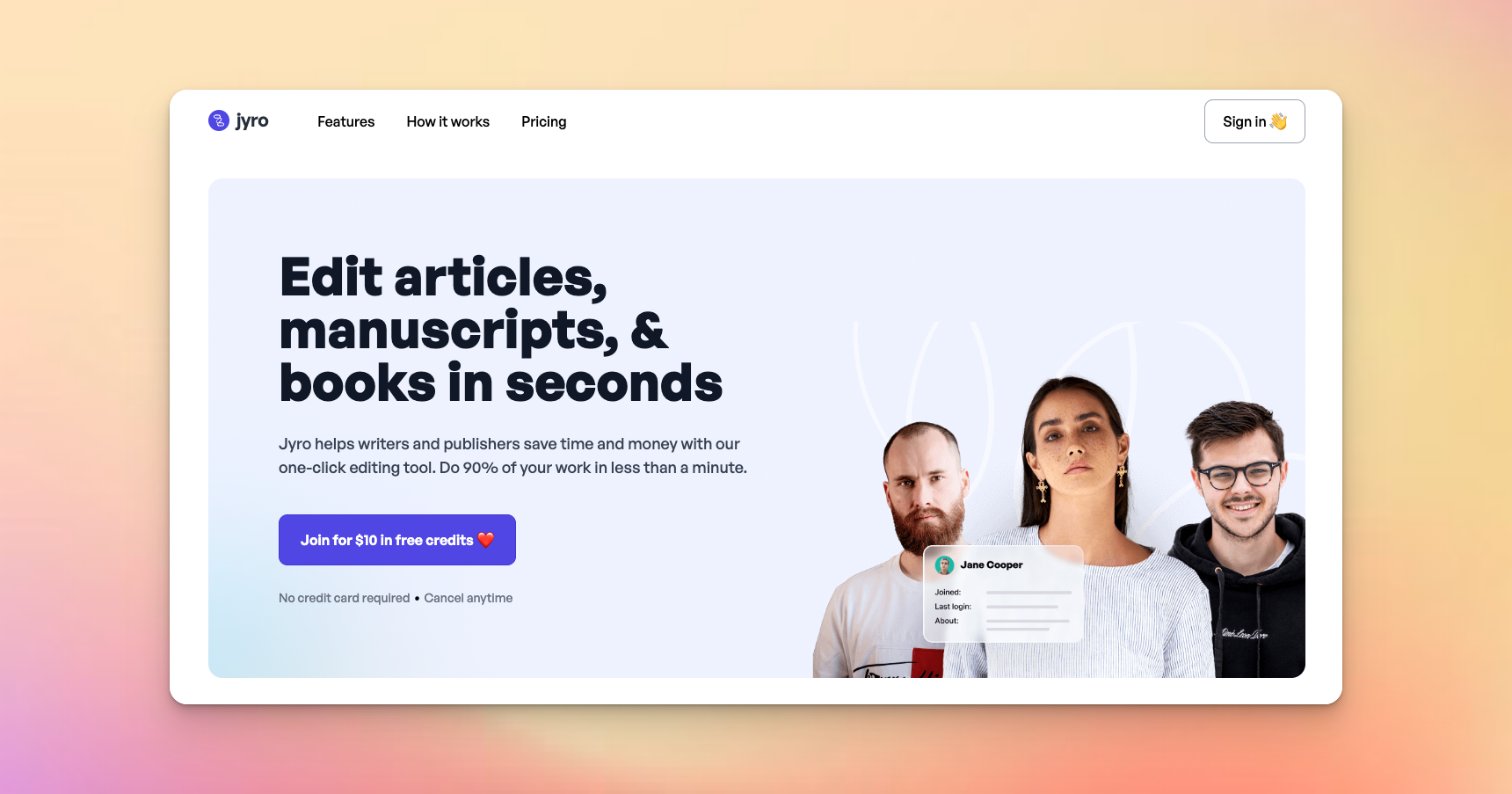

1SecondCopy

Given my relative success commercializing AI, I started looking for other opportunities. Like many, I had explored GPT-3, and was already using it infrequently to write copy, or document changelogs.

As I began using it more often, I found myself wondering whether it was possible to automate my freelance job.

It wasn't: GPT-3 was mediocre at code. But it turned out to be great at writing longer form content, like website copy and blog posts.

So, on another whim, I set up profiles on a variety of freelance websites, like Fiverr, PeoplePerHour, etc, and began offering content writing services at bottom-barrel prices using GPT-3 (~$0.02/word).

Unsurprisingly, when you offer something that cheap, people bite. It started out as just a interesting hobby, but I received a handful of gigs that week, which led to me investing more time into it, and I later developed a script that would take an outline and turn it into a rough article to keep up with the demand.

This continued for a few weeks.

At that point, I started pricing higher—around $0.05/word—and my more discerning clients were beginning to notice quality issues. Due to limitations of the model, it was difficult to coherently weave paragraphs together into a larger narrative; you could generate a paragraph or two at a time, but usually those paragraphs didn't make sense in context.

I spent weeks on a solution, and eventually gave up on solving it with technology.

Instead, I started looking into hiring editors, and tasking them with connecting the paragraphs manually. It was less money up-front, but I found I was able to charge significantly more.

Anyway, our rates continued increasing until they were ~$0.10/word. At one point I was making ~$3,000/month, after which I realized it made sense to pursue this as a business.

I discussed this with a handful of friends. One in particular—an intelligent fellow who was manufacturing USB-chargeable arc lighters—made a brilliant suggestion on project management infrastructure, and I decided to partner with him.

We began hiring in earnest, building the sales funnel, and, pretty much, putting together the rest of the company.

The first few months were rocky, owing mostly to a trip I was on at the time, but my partner, Noah, picked up the slack. He also helped us hire overseas (Philippines) staff, which were markedly more cost-effective than local contractors, and then built a better staffing model that distributed work to writers & editors.

Over the course of the next year, we were able to scale the company to a little under $100,000/month.

It was incredible! I distinctly remember us reaching $50,000 per month. This figure had been one of my lifetime goals, and to do it so quickly—and with (comparatively) little effort—felt life-changing.

But all good things come to an end.

The next year, ChatGPT was released publicly. When it went mainstream, many of many of our clients understandably became skeptical about AI-generated content.

This forced us to increase the proportion of manual output : AI output, which impacted margins considerably and forced us to scale back the business.

On the flip side, it also forced us to scale our team, and that has been one of the most meaningful things I've ever done—so not all bad!

Today, the company continues to operate (although in a less automated fashion than before). Am deeply thankful for the relationships I've built here.

LeftClick

I knew that 1SecondCopy was essentially knowledge arbitrage, and at some point it would have to come to an end. ChatGPT gaining mainstream attention implied that our best-before date was probably arriving soon.

So Noah and I began thinking about alternative business models to hedge against the rise of LLMs in content writing.

One of those business models was selling AI and process automation to digital services companies similar to 1SecondCopy. We figured that, given the inevitable proliferation of AI and related technologies, it was akin to a gold rush. And in a gold rush, there's always plenty of money to be made selling shovels.

Plus, I really like systems! Architecting a business is probably the most enjoyable part of building one, and showing clients a fully automated solution to a problem they're currently spending tens of thousands on is just fun.

Pre-productization

After a few weeks, we settled on an AI consultancy called LeftClick.

We attempted to hire a few contractors, thinking the business model would be similar to our content writing company: we'd onboard a new client, they'd give us a brief of what they wanted, and we'd fulfill it.

But things were a lot tougher than expected.

Content is relatively simple, from a service standpoint—you have a 'writing' step, an optional 'editing' step, and you're done. In contrast, automated AI systems have significantly more complex scopes, and where the responsibility of one person ends and another person starts is hard to determine. Hiring is thus difficult.

Additionally, the complex nature of most systems means you need people with specialized skillsets: they need a fair amount of technical knowledge to build, and business knowledge to deliver. But technical and business knowledge are usually at odds with each other, and, try as we might, we couldn't find good people with both at reasonable enough margins to scale.

A few months went by like this, with us at middling levels of revenue (~$25,000/m). Despite our best efforts, we couldn't make it work. Noah ended up suggesting that there might be better opportunities elsewhere, and I reluctantly agreed. We ended up splitting.

Post-productization

When Noah and I parted ways, we divided up our clientele. I ended up keeping the company, at first intending to shut it down at the end of the year.

This was out of necessity to keep billing the handful of clients LeftClick had accrued. I wanted to minimize the perceived impact on their experience. I mean, think about it from my perspective: although most of the company had just vanished, there were still a handful clients under the umbrella of "LeftClick" that had projects they needed fulfilled + were willing to pay for them!

I'm not in the habit of saying no to money, so I continued managing them.

During this period, one of those clients requested a system very similar to one I had already built for someone else. So, to get myself started, I figured I would just duplicate the template from client A over to client B, then make some minor adjustments.

All in all, this took me perhaps thirty minutes to do. I made ~$1,000. And this led to a lightbulb going off in my head.

In fulfilling that project—and making, frankly, a stupid amount of money per unit time—I realized that, contrary to what Noah and I had previously thought, the problem was not with our industry. The problem was with our specific implementation of the business model.

Let me explain. Up until that point, we had treated our automation business like a software development company. Like any software development company, we focusing on acquiring clients with complex, custom scopes, because the up-front cost of each project was usually higher, and we figured that was the straightest line path to making us more money.

Naturally, then, to fulfill these enormous projects at any level of scale, we had to hire skilled people. And hiring skilled people was the problem we couldn't solve.

After my recent experience, it was clear that not all client projects have to be like that. I mean, in this case, I merely duplicated a template, took thirty minutes to edit it, and it made me over a thousand dollars.

And while this $1,000 was not as high as, say, some of the $9,000 custom projects we had done previously, it took me around 1/100th of the time. Mathematically, around 11x my previous labor productivity. Not bad!

So, I asked myself: what if I simply looked for clients that wanted that sort of system --> duplicated it over and over again? What if I just.. didn't do custom projects?

If you have any sort of consulting knowledge, I know this seems silly in hindsight. You've probably have been yelling at your screen for the last few minutes. But keep in mind I had never ran a consultancy before, and despite my success with 1SecondCopy, I did not understand even the most basic tenets of productization.

Anyway, to summarize: instead of focusing on broad AI automation offerings, I broke down my services into a small set of very leveraged templates (like one-and-done cold email systems, or one-click CRMs), and then offered only those services to clients.

I scaled this to a little over $72K in one month. I did end up hiring an on-and-off virtual assistant for help with some tasks, but all of the work was my own. It was incredible, very freeing, and—frankly—insane that I could generate that much money solo.

Information products

I don't mean this to dissuade anyone from starting an agency, but the model is difficult to scale reliably. The reason for this is that your income scales with time—and whether it's your time directly, or the time of your team, it is still... time. Plus, hiring is difficult, and coordinating a large enough group of people to consistently fulfill hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of projects is non-trivial.

Accordingly, the slope of the revenue : effort graph tends to be small & growth is linear at best.

So after my scaling to $72K, I earnestly tried to push further myself, but I found a significant amount of resistance. Monthly churn, the nature of microservices, the occasional fires, & the fact that I had only ~60 hours in a week (and my clients wanted most of them) were to thank. I certainly tried to work harder, faster, more efficiently; there was, however, clearly an upper limit to what I could do.

I considered hiring. But since I was still coming off the high of shifting my business model from a custom software development agency -> leveraged consulting, though, I opted to try something different first, and figured I could always hire later if necessary.

What that was: I tried to answer the question "assuming I am not wedded to this business model, what else can I do that might scale further than my current approach?"

It was a very fruitful question! Here's rough map of my thinking below:

- Implementing custom software projects took me to $X.

- By going up one level of abstraction (custom -> templates), I was able to make $Y.

- So if I go up one level of abstraction again, could I get to $Z?

- If so, what is that level of abstraction?

Hindsight is 2020. Obviously info products!

I didn't reach this conclusion immediately. It took a few days. But eventually, I started playing around with the idea of course products in my mind. After all, they were scalable, mostly divorced from time demands, and much higher leverage than what I was doing at that moment.

Additionally, they were pretty cool. Instead of implementing a system, I could teach people to build that system in a fraction of the time. These people could then build hundreds, if not thousands as many systems in total, which would have a more significant impact on the economy.

More change + more money!

YouTube

~6 months into scaling LeftClick on my own, I begun publishing on YouTube. My rationale was simple: I was tired of acquiring most of my leads through cold traffic. I was great at marketing to them, but sales calls were always (at least initially) adversarial, and my growth always scaled with my time. I didn't like selling that way, and I didn't like having to spend the bulk of my day on calls.

Ideally the people I'd talk to would like me and already want to buy. A sales call would just be a confirmation of details; perhaps some authority building; etc. The real ideal was never having to talk to anyone at all, though I was not thinking about that just yet.

Anyway, I did not come up with the YouTube idea. I got it from a good friend of mine, Zak, on a vacation to Mexico, when we were discussing distribution mechanisms and different business models. I have him to thank for most of my subsequent success on the platform.

During this period, I experimented with posting consistently on a variety of topics. At first, my videos were general, mostly related to the work I was doing that day. Eventually, though, I found patterns in performance—when I included the term "Make.com" in the title or the thumbnail, I received more views. Pretty straightforward.

So I started doing that, and after feedback, eventually realized that "Make.com for money" was my key differentiator. I started creating free courses on this topic, appropriately named "Make for people who want to make money", and this scaled my YouTube channel.

To be clear: I saw virtually no growth for the first couple of weeks. My videos averaged a handful of views, perhaps fifty. And this is where the majority of content creators give up. There's this "great filter", and the only way to push through it is sheer will and a stubborn amount of volume.

Eventually, my persistence paid off. I started seeing the fruits of my labor in the form of ~30 subscribers/day, then ~50, and then ~200 (avg) in fourth week. My channel hit ~3,000 subscribers by the end of Month 1.

Make Money With Make

Around three months in to my YouTube channel, I was on top of the world! Though I had taken my foot off the gas, my earlier efforts had compounded, a few of my videos had gone viral, and in sum I had scaled to ~10,000 subscribers.

What's more: given the social proof and the absurd number of "watch minutes" I had accumulated, my videos were now doing the majority of my sales work.

They were getting people interested, nurturing them, and inoculating against various objections ahead of time. Also, they were character building. This all which led to my sales calls shifting from predominantly cold -> predominantly warm, and my average order value spiking.

Around this time, I noticed my audience start to shifting. Before this period, it was predominantly people that were interested in the technology (Make.com). But after I achieved sizeable growth, it became people interested in replicating my business model (an AI automation agency with Make.com as the primary platform).

Accordingly, comments on my videos changed from technical questions to requests for coaching, more courses, and, ultimately, a private community.

I had heard of that term before, but never really looked into it. When I had considered information products before this, I was always envisioning the standard "course" rigamarole, since that's what I was used to from my college days.

Also, it seemed a little silly to me. Communities were, by and large, significantly cheaper than one-off online courses—their only benefit was recurring—so if I was going to create an information product, why would I sell one at $30/m when I could do it for $300 a pop?

But the volume of these comments ramped up. I remember seeing notifications on my phone after publishing one of my videos, and something like five comments in a row said variations of "make a community! we will buy!"

I hope it's clear at this point, but I am not in the habit of ignoring obvious opportunities. So, around a month after these comments started, I put together a (very simple) draft of what would eventually become Make Money With Make, my mid-ticket automation product.

I had never built anything of the sort before, and was naturally very skeptical that I would get interest. A big part of me did not believe products like these were valuable, having never been in a community myself.

So I set my price very modestly, at $28/month. I placed a "cap" at 400, thinking I'd be lucky to get a quarter of that. And I made a few intro posts, inviting friends and people in my network from Twitter for free.

Then, I added the link to a few of my highest-performing videos before logging off for the night. I did this specifically so that I would not have any control over the outcome, and so that, if I woke up the next morning with no success, I could scrap the idea while having lost nothing for it.

As an aside, this is, funnily enough, how I release most of my YouTube videos now. Very late at night, so that I can't see the initial performance until I wake up and it's too late to meaningfully change it. I force myself not to check the outcome—very bad habi.

As you can expect, I ended up getting much more traffic than I was expecting. When I woke up the next morning, I was making nearly $1,000/month.

My jaw dropped! I texted a screenshot of the member count to all of my friends, immediately added the link to the rest of my videos, and began working on providing the value that I had teased in the "About" page (namely, a 14-day course and a bunch of templates).

Waitlist

The number of members skyrocketed quickly. Given the growth, I began raising prices, thinking it would slow the volume down and help me bring the growth to a standstill at around 400.

I learned a rough lesson that week: the relationship between supply and demand is very different in the real world versus what they teach you in economics class.

As I increased prices, demand went up, not down. Owing to the perceived scarcity and the idea that earlier members would be 'grandfathered in' to the price, my average signup volume spiked. First a few dozen a day, then 50, then 100, and by the end of ~10 days, I had hit the 400 member cap at a final price of $128/month.

At the time, I was generating ~$50,000/month selling agency services. By creating this community, I had immediately grown my bottom line by more than 50% in a week. It was by far the quickest revenue growth I had ever seen (in absolute magnitude terms), which led to a few sleepless nights and a fair bit of concern over how I was going to fulfill all of these members. 400 people was a lot!

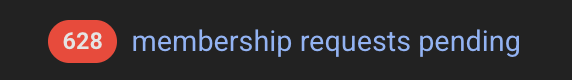

A couple of days later, I logged into Skool and noticed a new, peculiar red icon at the top of my screen, alongside the text "Membership Requests Pending". I frankly couldn't believe it—clearly there was more demand for this sort of product than I thought.

Scaling to $100,000/month

The next few months were a whirlwind. I had no idea how communities worked, and now I suddenly found myself in possession of one of the larger ones (by revenue) on Skool.

I did not have a roadmap, or any sort of course, on how to manage communities. So I made a number of mistakes initially. In hindsight, I probably should have looked to people that were doing better than I, but I was too busy caught up in the work, and I preferred to approach things from first principles.

In business, the first principle is always talk to your customers!

So I made it a point to spend at least an hour on my community every morning, responding to every thread, DMing people that joined, recording Loom videos to debug technical questions, etc.

Since I wasn't part of any other communities at that point, I didn't really have anything to compare that volume to. But, as it turns out, the frequency with which I was engaging with people was fairly unique (especially at the time, May-July 2024).

I.e most other community members spiked traffic -> engaged with new members for a few weeks -> faded out, preferring to pass things off to a manager. I did not, believing that the time I spent responding to people manually was probably good time—it'd buy me upsell potential later on, improve my perceived authenticity, and also teach me about the main problems my members were suffering from.

I firmly believe this was the right move, and almost entirely the reason why, at the time of this writing, I am the third largest community by revenue on Skool!

To be clear: of course it's a ridiculous amount of work to do this. But has there ever been anything worth doing that hasn't involved a ridiculous amount of work?

At the time, I was sure there are more scalable implementations of the community model. However, I figured that the goodwill and reputation that this would buy me would outweigh that. To borrow a phrase from the wonderful Paul Graham, "do things that don't scale."

Eventually, this culminated in me making over $100,000 profit in October. Given that I had been chasing that illustrious six-figure-monthly mark for many years, it felt like a dream come true!

This is ongoing—I'm writing the rest as we speak!

Goals

To be frank, a lot of my life has been pretty aimless. I'm not sure what I want to do with it, and this is something I'm trying to change.

I know, absolutely, that I want to have a major impact. Whether it's out of a desire for legacy, or it's just some animalistic need to accrue resources, I don't know.

I think most people feel similarly, and are just unable (or afraid) to articulate it. But coming to terms with your feelings seems necessary to satisfying them, so I'd rather put it out in the open.

Technology

There are many ways to achieve impact, but the most likely is probably something to do with technology. You don't have to be a genius to see the transformative potential of technologies like GPT-4 or Sora.

I don't like academia, or research, so it's unlikely I'd make meaningful contributions on the theoretical end. I do like entrepreneurship, and I'm pretty good at it, so I'm leaning towards "starting or joining a company that revolutionizes X", where X is some important process or facet of our culture.

I have no clue what that might be as of yet, though.

The near-term

In the next few years, money will obviously be important, so I'm acquiring more of it. I set a realistic goal of $2M in annual profit (~4x greater than my current all-time-high), simply because selling a company of that size guarantees retirement. It would also let me take care of my family and my close friends.

I may achieve this with LeftClick, or another vehicle. I'm not beholden to either, though.

Wrap-up

I hope you now know a little bit more about me and why I do the things that I do! This list wasn't exhaustive—I've began a variety of other businesses, and had a handful of temporary jobs—but none were particularly remarkable and I wanted to keep things brief.

It goes without saying, but omitted here are a tremendous number of personal and professional relationships I've made that have shaped my worldview considerably.

One important thing I learned about myself while doing this exercise is how much each of my career milestones have revolved around specific people. My most successful companies were ones where I partnered strong and early. So I'm going to make it a goal to consciously build those kinds of relationships as often as possible, and put myself in situations where serendipity is more likely to occur.

If you'd like to contact me, for career-related reasons or otherwise, send me an email at nickolassaraev@gmail.com. Please follow up if I don't get back to you (I get a lot of spam).

Other miscellaneous facts about me

- My Myers Briggs personality type is ENTJ-A.

- I'm agnostic. I think that whether God exists or not is, by definition, unknowable, and that any evidence for God can equally be understood as evidence that humanity doesn't yet grasp a scientific process.

- I think radical life extension is possible, and maintain a rigorous diet and exercise routine to maximize the probability of achieving it. I was featured in Popular Mechanics for my beliefs on the subject.

- I love electronic music. At the events I promoted, I'd routinely perform. My music taste is probably best described as orchestral electronic (example).

- I grew up in Vancouver, B.C.

- My favorite book series is the Sun Eater Sequence. The cover art is lame, but don't be fooled—Christopher Ruocchio, the author, has some of the best prose I've ever read. Every chapter is like poetry.