Prosthetics have seen significant improvements over the last few half-century. Science has taken us from clunky, Frankenstein-esque jig systems to modern myolectric and neuroprosthetic products that use electrical stimulation from your muscles or nerves to move.

In this simple guide, you’ll learn simple explanations for how different types of prosthetics work. We’ll start with older technologies and work our way forward through time.

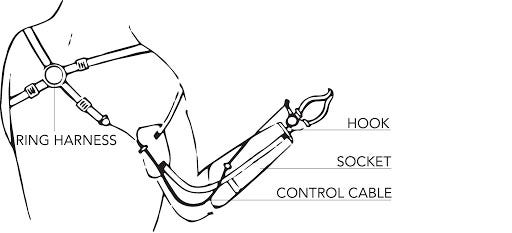

Body Powered Prosthetics

Body Powered Prosthetics are still, by a large margin, the most commonly used upper prosthetics today. Aptly named, these prosthetics are powered by movements of the body. Most use a cable system that opens and closes a mechanical hand when tensioned. When the arm is stretched outwards (so as to pick up or grab an object) the hand is pulled open. When the arm is stretched back, the hand closes.

This simple-seeming functionality has wide reaching benefits for those without limbs, allowing them to perform (albeit with some difficulty) most of the requirements of day-to-day living. The advent of the first body powered cable system was likely the single biggest improvement to the quality of life of pre- and post-amputees since the discovery of penicillin.

Myoelectric Prosthetics

Myoelectric Prosthetics are exploding in popularity. Soon to be the most common type of prosthetic worldwide, they allow incredible control over artificial limbs, providing amputees improved function, comfort, and durability. They work by taking advantage of the electrical signals produced by your muscles during contraction.

When you flex a muscle, waves of electrical potential sweep through its cells and become detectable on the skin. By placing sensors on the prosthetic interface, these signals can be relayed to a control unit for decision-making.

The strength and frequency of these waves depend on the intensity with which the muscle contracts, allowing a myoelectric prosthetic to change the strength of movements based on signal amplitude. This means you’re not just relegated to opening or closing your hand anymore — myoelectric prosthetics offer you significantly more degrees of freedom, allowing you to more closely approximate the function of a biological limb.

Neuroprosthetics

Neuroprosthetics rely on neural interfaces between the prosthetic and the human brain. They often connect directly to nerves or bone, oftentimes requiring dedicated surgical implantation of neuronal sensors.

These surgeries are incredibly invasive, but offer unprecedented, native control over prosthetic limbs. Once they’re connected to your brain, the prosthetic becomes a direct extension of your motor system.

Neuroprosthetics work similarly to organic limbs. When you want to move an organic wrist, for example, electrical signals that originate in the motor cortex travel down nerves that innervate the muscles of your forearm. These muscles contract, leading to tension on the wrist that pulls it towards your body.

When you want to move a prosthetic wrist, electrical signals that originate in the motor cortex travel down nerves that would have innervated the muscles of your forearm. Surgically implanted sensors read these nerves, and a control unit translates their signals into meaningful movement data. This data is transmitted to the prosthetic, which then activates the necessary motors to affect the desired movement.

Neuroprosthetics are undoubtedly the future. However, public willingness to accept non-necessary surgical interventions may slow adoption. As always, society will dictate how soon we choose to progress — for better or for worse.

Congratulations! You have a strong understanding of the basics behind how prosthetics work. You can now quickly improve your knowledge by performing a deep dive, educate friends and family, or make an educated decision about which prosthetic device to choose for yourself.

As the field of prosthetics matures, we’ll continue to see incredible advances in functionality and power. Very soon, having a prosthetic might not be seen as an impairment — instead, it’ll be seen as an advantage!